1. VAUXHALL MOTORS LTD - BACKGROUND:

To fully understand how Vauxhall got into such difficulties that a takeover was the only option to stay in business it is necessary to go right back to the early days of the Company and trace, step by step, where things went wrong.

In 1905 Vauxhall had moved its entire operation to brand new premises at Luton which included both the marine steam side of the business as well as the manufacture of motor cars. Within months Vauxhall had amalgamated with the West Hydraulic Company Ltd to form the Vauxhall & West Hydraulic Company Ltd with a management board increased from six to nine. This meant the new Company was producing a huge range of very diverse products and in a short time it was felt by the Board that some sort of rationalisation was required because the diversity was not producing any significant benefits. With the future of the motor car still uncertain and the Board were unwilling to “put all their eggs in one basket” so the motor car manufacturing side of the business was legally separated in 1907 to form Vauxhall Motors Ltd. By 1908 it was clear the future lay in the production of motor cars and the Vauxhall & West Hydraulic parent company had its capital reduced from £50,000 to £25,000. The parent company continued and limped through World War I but was finally wound up in 1918, the only two Directors left were W Gardener from the original Vauxhall Iron Works and Benjamin Turner, one of the original owners of the West Hydraulic works.

The formation of Vauxhall Motors Ltd in 1907 gave a balanced leadership to the Company for the first time, Leslie Walton was appointed Chairman and joint Managing Director with Percy Kidner Walton owed his position to his financial background and experience as well as being a major shareholder in the Company. Percy Kidner had joined the Vauxhall Iron Works in 1903 was an experienced engineer and later became a works driver in competitions, he held 2,000 preferential shares and replaced John Chamber as joint Managing Director when Chambers left at the end of 1903. The other key member of the Board was Frank Hodges who was appointed Consulting Engineer. It was clearly Kidner & Hodges who pushed for the motor car side to be prioritised and eventually separated but Walton’s business acumen was on hand to ensure the Company was kept on the road of solvency and profitability. Under Hodges engineering leadership Vauxhall made cars of no particular distinction, unlike those of Laurence Pomeroy whose influence began from 1906 onwards, but the relatively pedestrian Hodges designs proved to be profitable. Production increased gradually, especially form 1909 onwards, but this required constant works reorganisation which reached a peak in 1911 and the associated costs meant profits for that year fell.

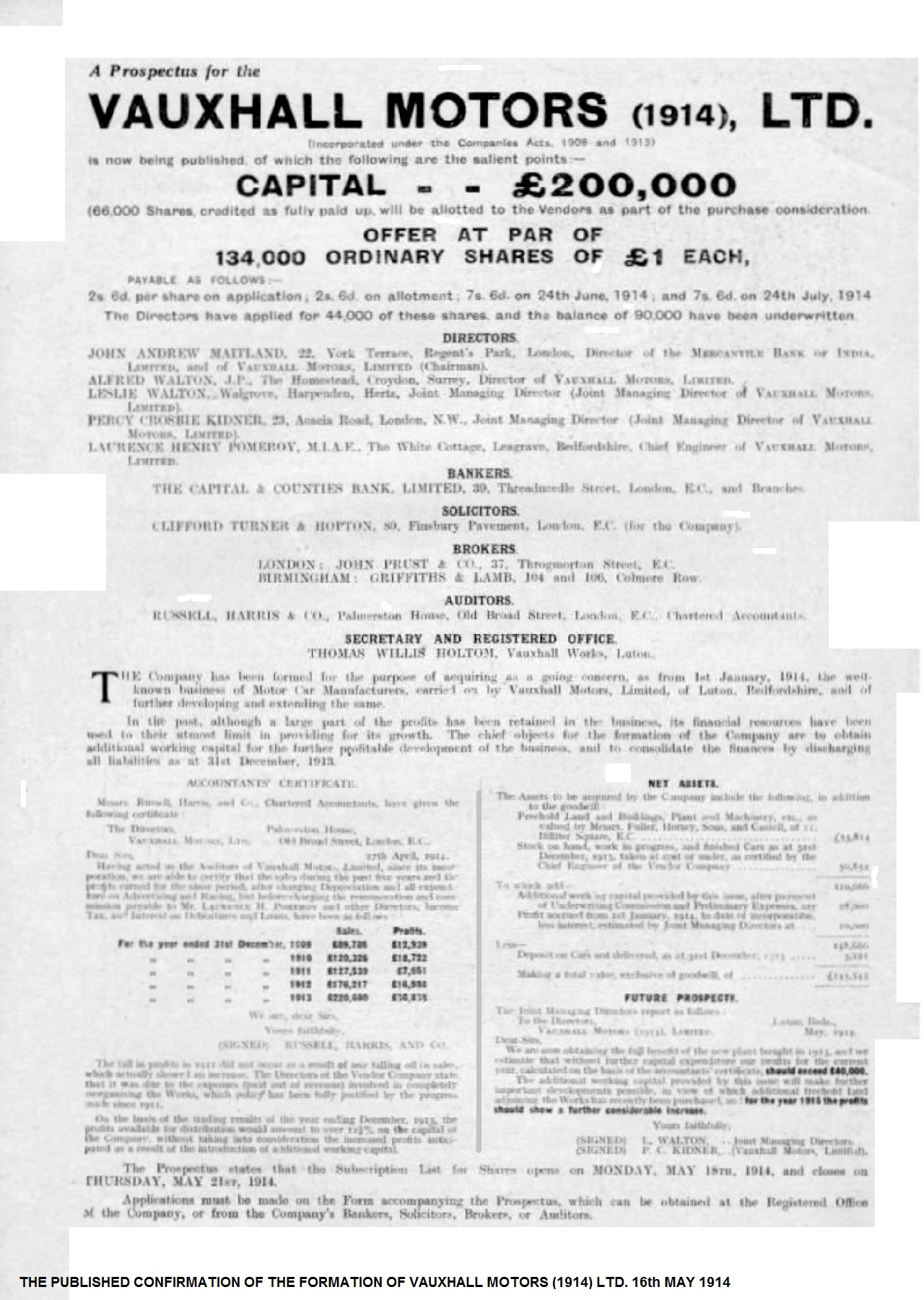

The Board became more concerned over the next two years that the Company was producing well below the factory’s theoretical capacity despite the use of the most modern machinery. In 1914 the Company was reconstituted & recapitalised under the new title of Vauxhall Motors (1914) Ltd. Hodges had gradually become more sceptical of the commercial value of sporting successes unlike Pomeroy & Kidner. Vauxhall cars were in great demand following the achievements of Pomeroy’s cars but Vauxhall could not meet the demand, the potential works capacity was present but external capital was lacking. Vauxhall was wholly unsuccessful at the time in attracting capital investment which meant much of any expansion was reliant on debenture issues and the reinvestment of profits as was the case in 1911. Even before the 1914 reorganisation shareholdings only amounted to £19,297 out of a possible issue of £30,000. This slow accumulation of capital was not a problem prior to 1908 but once demand increased significantly it became a handicap. The nominal capital of Vauxhall Motors (1914) Ltd was issued at £200,000 in ordinary shares of which £66,000 were to be taken in part purchase of the old Company. This left £132,000 to be issued of which £44,000 had been taken up by the Directors, the result was a considerable rise in Vauxhall’s capitalisation. The reorganisation also removed all existing Directors who were replaced by Leslie Walton, his brother Alfred Walton, Laurence Pomeroy and a banker John Maitland. Walton & Kidner were the joint Managing Directors of the new Company. Profits were projected to be £40,000 in 1914 and a further increase in 1915, World War I scuppered both targets, in fact profits fell to £21,173, this was attributed to 150 staff out of 700 joining the war effort. Following the death of John Maitland in 1914 Leslie Walton was appointed Chairman. Vauxhall was effectively saved by orders from the War Office which took Vauxhalls entire output, this was for just one type of car – the 25hp which was used as an army staff car. In addition, both the Admiralty and the War Office warded large contracts to Vauxhall for the manufacture of ammunition fuses, this required the building & equipping a completely new factory and by 1916 all available land adjoining the works was purchased with a view to further extensions. Finance was raised by the issue of a further 100,000 ordinary shares and new offices and stores were added as well expansion of the running shop. With guaranteed prices

slightly ahead of the pre-war market prices ensured healthy profits, by the end of hostilities a further £100,000 of shares had been issued bringing the total to £400,000 and since 1915 an annual dividend of 10% had been paid.

The downturn in profits for 1919 was not totally unexpected but was viewed by the Board as a temporary setback and largely due to the end of wartime contracts and the conversion back to peacetime production. Although profits did increase in 1920 to £35,222 on sales of £812,579 from 1921 onwards the Company began to sink further and further into a financial crisis. There is no one reason for this, it was a combination of many factors, unsound management decisions, over expansion towards the end of the war, the production of the wrong type of models, £18,305 written off after closing the Russian sales organisation and the resumption of expensive competitive racing, an immediate short term post war economic depression and a fundamental change in the car market towards smaller, cheaper models. Vauxhalls capital was increased by £200,000 to £600,000 and an additional 1.5acres of factory floor space was added, 320 new worker houses were built nearby, in 1921 17acres of playing fields were purchased for worker recreation. Finance was provided by bank overdrafts to the value of £246,000 in 1919 and by the issue of £3000,000 on short term notes repayable in 1925. Probably the foolhardiest investment by Vauxhall Management was £90,000 in S F Edges – AC Cars Ltd which went into liquidation shortly after with no redress for Vauxhall. Although the selling price for cars increased in a short boom period in 1919-20 this was offset by large increases in material and wage costs.

When the market slumped by nearly 50% in 1920/21 the mass producers such as Austin and Morris were able to produce small cars with a small profit margin but because of huge production volumes still remain viable. Vauxhall as an established and well respected producer of quality cars in a similar vein to Sunbeam and Humber, although they lagged behind in some areas such as using side valves instead of overhead and front and not all wheel braking. However, Vauxhall were like their competitors in that they all suffered from a common, and fundamental, problem; the low productivity which prevented price competition with producers such as Morris, Austin and Ford, which had massively intensified in the early 1920s. Vauxhall were forced to reduce prices substantially but Leslie Walton blindly still maintained that the large car market would rebound quickly and prices would return too normal, in spite of Vauxhalls loss of £221,758 in 1921. With heavy capital commitments and debts in the form of bank overdrafts as well as short term notes, the Vauxhall Board reluctantly turned to the production of a smaller vehicle which they hoped would increase sales. The result was the M Type 14/40 launched in 1922 at a selling price of £650, well below a normal Vauxhall selling price, unfortunately Vauxhalls rivals such as Humber, Sunbeam and Crossley all had the same idea to combat the same problems faced by Vauxhall so instead of having a unique market to themselves the market competition was the same but just lower down the price scale. The 14/40 became the mainstay of production until 1925 with 2,000 workers producing 30 cars per week. An attempt to remedy this was made by Vauxhall early in the decade by reorganising the Luton factory in a half-baked attempt at an assembly line but only for the fitting of engines and chassis ancillaries. Despite this, production was still hopelessly slow compared to the full mass production techniques used by the largest producers such as Ford and Austin. Some savings were achieved by withdrawing from completion events in 1923 but there was still a chronic lack of production cost control compounded by still producing cars for a market that was fast disappearing.

2. VAUXHALL MOTORS LTD - THE PERILOUS FINANCIAL POSITION:

In 1925 Leslie Walton, Company Chairman, stated that Vauxhall was not equipped, trained or had any desire to produce large quantities of mass produced cars and would continue the policy to produce a “reasonable” number of high class cars at a “moderate” price and this must always be our policy. It is clear from this that the Vauxhall Board still did not grasp the reality of what was happening around them, the Company was well on its way up a blind alley.

In any event it was now too late, Vauxhall did not have the capital available at the time to make the huge investment that mass production would have involved. The prospect was also looming in 1925 of the redemption of £300,000 Short Term Notes taken out in 1920 to keep Vauxhall afloat and, in addition to large bank overdrafts, meant the financial standing of the Company was beginning to crumble. Walton called a special shareholders meeting where he stated that the improvement in profitability for the previous two years was not enough to reduce the overdrafts or set aside funds for payment of the Short Term Notes. The company was backed into a corner and as a result it was proposed to create and issue First Mortgage Debenture Stock for the sum of £350,000, this effectively meant mortgaging all of Vauxhall’s fixed capital and assets. The shareholders had already seen the capital reduced from £600,000 to £300,000 by writing off 10/- shillings on each share in 1923 and none had received a dividend since 1919. However, the shareholders had no real choice because if they failed to accept the offer Vauxhall Motors Ltd would go into immediate liquidation.

3. GENERAL MOTORS LOOKING FOR AQUISITIONS OUTSIDE THE US:

General Motors Overseas Operations (GMOO) had felt sufficiently confident in the British car market that it had set up an assembly plant in 1920 at Hendon Aerodrome to build cars from imported CKD (Completely Knocked Down) kits from the US, these included Buicks, Cadillacs, Chevrolets, La Salles and Oaklands. CKDs were used because a lower import tax was levied compared to importing complete vehicles thus giving GM a price advantage over other imported vehicles. The operation did suffer from the same round of competitor price cuts of 1921 and the growth in low price models from Morris, Ford and Austin cut into GM vehicle sales. In 1924 a survey was conducted by the head of GMOO, James Mooney, and clearly highlighted the taxes on engine size, insurance and servicing costs placed the cheapest Chevrolet at a £112 price disadvantage compared with an equivalent Austin, not much in today’s money but a huge difference in the 1920s.

This was the incentive for General Motors to give the go ahead to GMOO to seek the acquisition of a British motor manufacturer, in the meantime the Hendon plant was turned over to the more profitable production of Chevrolet trucks with locally built bodies, ironically it was this vehicle that was later to form the basis of the first British built Bedford truck by Vauxhall.

After assessing all their requirements GMOO chose Austin Motors as being the ideal operation to take over. Negotiations started in 1924 and were initially favourable, Herbert Austin was amenable as his company was having difficulties in raising capital for its own expansion plans but there was always the backdrop of criticism from the national and motoring press which resented the prospect of a well-known British companies passing into American hands. After months of deliberations in early October 1925 the plan was scotched by dissenting Austin directors who opted for a more modest self-financed expansion plan rather than relent and go into American ownership.

4. VAUXHALL MOTORS LTD - THE TAKEOVER BY GM JUST IN TIME:

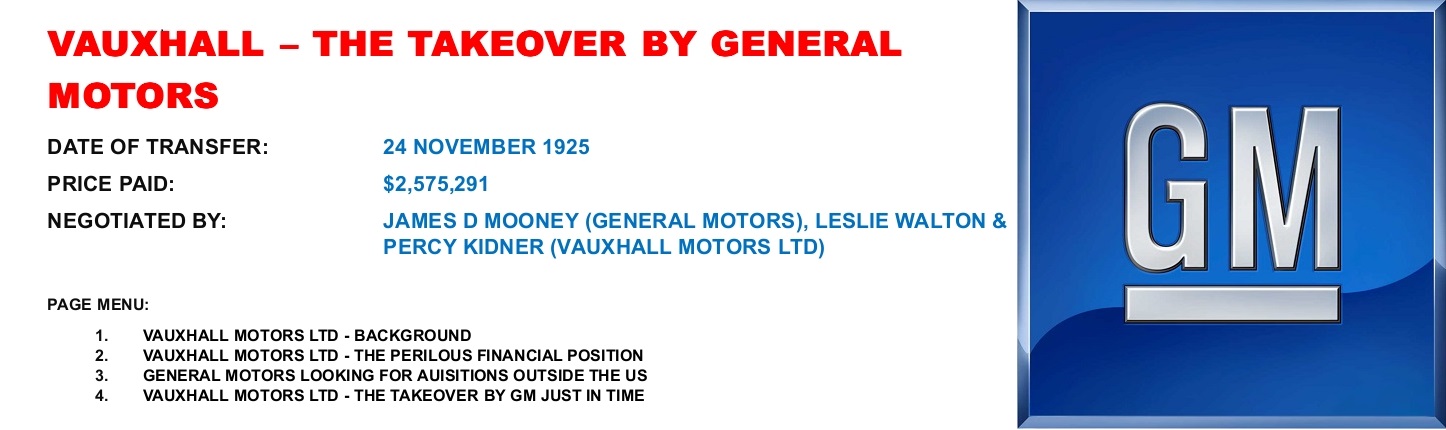

Wasting no time, on 21 October 1925 negotiations started with Vauxhall Motors Ltd. The issue of the First Mortgage Debenture Stock for the sum of £350,000 at 7% had not been very successful and the Vauxhall Board was more than willing to entertain GMOO’s offer of $2,575,291 for the purchase of all the ordinary shares. This enabled the 300,000 ordinary shares to return to their pre 1923 value of £1 each, former shareholders also had the option of purchasing up to 300,000 preference shares at £1 each with a guaranteed dividend of 6%. Old ordinary shareholders were paid a bonus of £210,000 which combined with the above made a total of £510,000 invested in Vauxhall. The deal was agreed in principle within days of talks starting and was completed in full on 24 November 1925, through Morgan Grenfell, GM’s Merchant Bankers, who had also dealt with the Austin proposal. A new seven-man board of directors was appointed on 16 November 1925; Four British - Leslie Walton remained as Chairman and joint Managing Director, Percy Kidner as joint Managing Director, and Board Directors Mr Bisgood and Mr Petch; Three American Directors were appointed – James Mooney also head of GMOO, Edward Riley assigned from the GMOO Hendon operation and Alfred Swayne from GMOO headquarters in Detroit.

Within General Motors in the US the deal received a less than favourable reception and vociferous disagreements over Vauxhall continued until 1928, major policy decisions were delayed by Alfred Sloan, GM President, who wanted to move cautiously until a clear policy had been worked out for all overseas operations. This caution did not stop GM trying to purchase Morris Motors Ltd for $11 million in 1926, but again they were rejected, and then to compound matters GM entered into an auction with William Morris and Herbert Austin for the bankrupt Wolseley Motor Company, a battle that Morris eventually won.

There were plenty of GM insiders who thought that a manufacturing presence in Europe was not needed at all but an added complication was the acquisition of Adam Opel in Germany on 30 March 1929. The strategy was the two companies would both compete with each other in the same way that GM divisions worked in the US but Opel

would be the base for European manufacturing and Vauxhall for Britain and the Empire which at the time covered 38% of the world. Unfortunately, financial losses at Vauxhall for 1927, 1928 and 1929 did not help Vauxhall’s case but the depression that followed the Wall Street Crash and foreign countries putting up heavy import tariffs gave General Motors an advantage with Opel and particularly with Vauxhall and their British Empire territories.

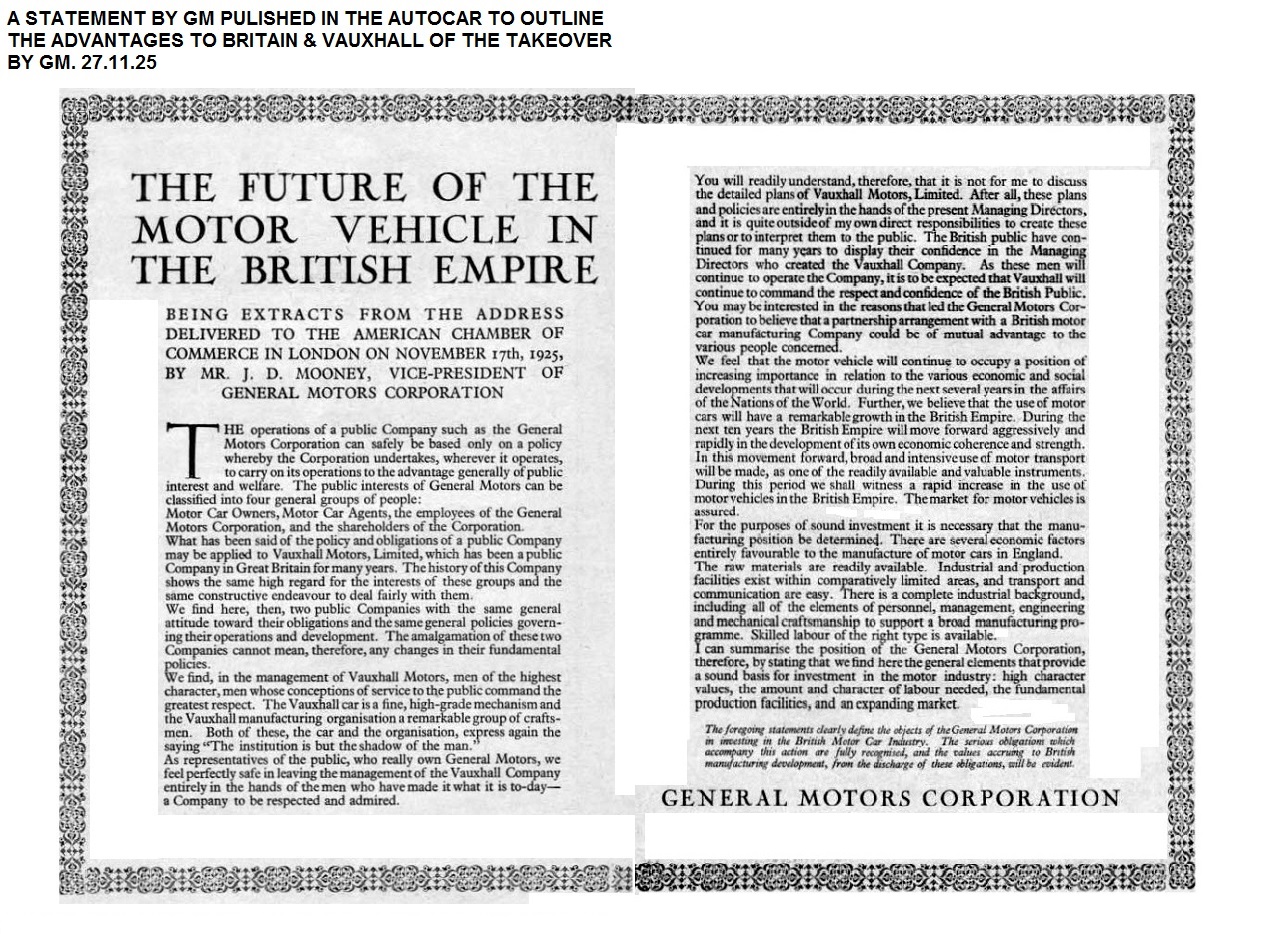

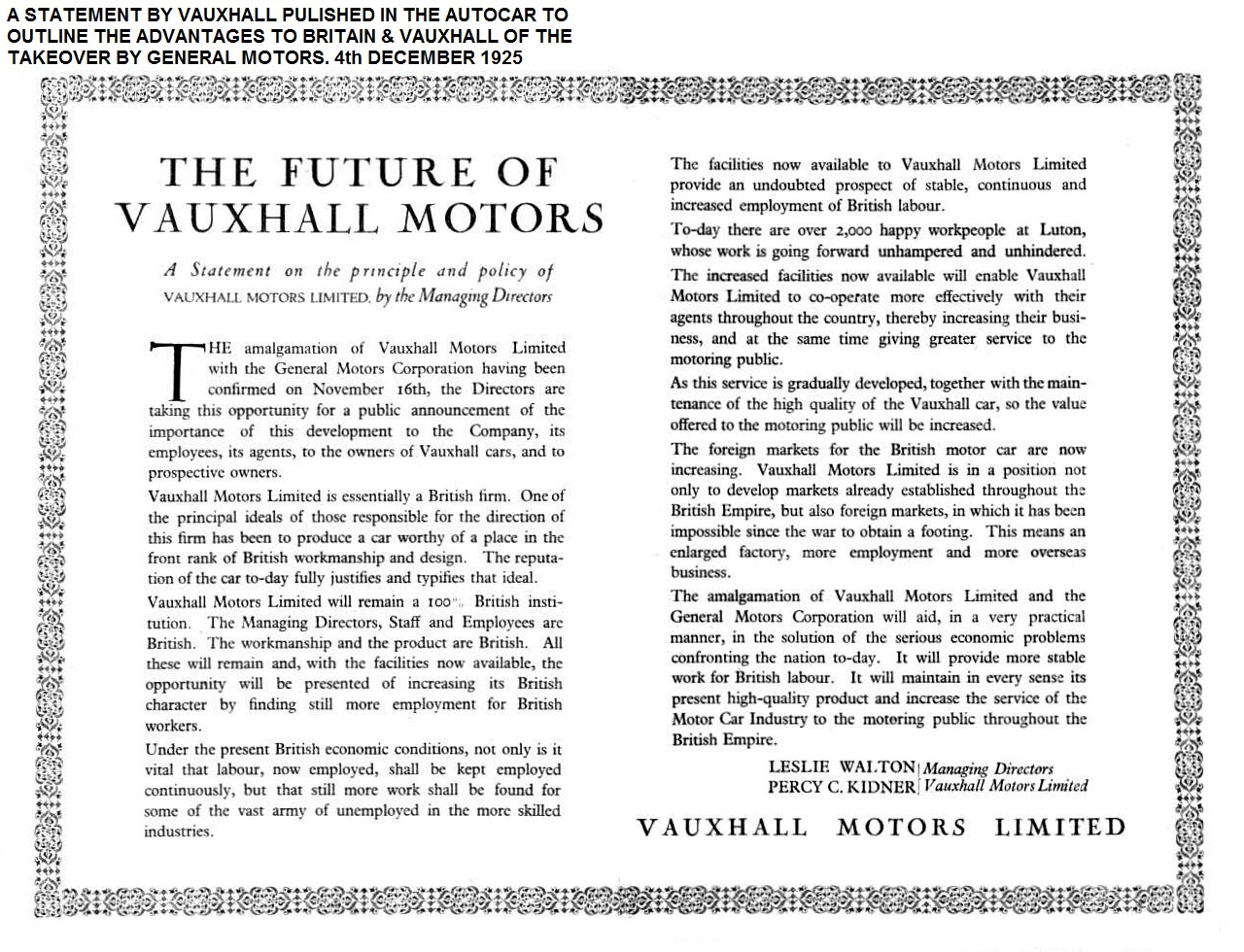

What was to have a profound effect on Vauxhall was the attitude of the press towards the Company after the takeover by GM. Most vociferous was Edmund Dangerfield the editor of “The Motor”, his attacks resulted in a double page advertisement in the magazine entitled “The future of Vauxhall Motors” which emphasised that it would remain a 100% British institution and the Managing Director, Chairman, staff, workmanship and product were British. Significantly it was only signed by Walton and Kidner. This did not stop the criticism and Vauxhall ended up withdrawing all advertising and loan of test cars for nearly two years. This atmosphere also dictated that the GM connection was not mentioned in any Vauxhall advertising and sales promotion for many years.

General Motors felt it was wise under these circumstances to have British nationals as the main company figureheads but despite this Mooney was anxious to have a senior GMOO man “on site” and to this end he appointed American born Bob Evans as joint Managing Director with Percy Kidner while Leslie Walton remained as Vauxhall Chairman, Evans was previously GMOO European Regional Director. Kidner & Evans shared the responsibilities of running Vauxhall uneasily, Kidner was a Vauxhall veteran and had assumed the American injection of cash would see the Company through a bad patch but that it would continue to produce large, high priced, high quality performance vehicles with a thoroughbred reputation. Maurice Platt, working for The Motor at the time, commented that Kidner was a robust car enthusiast but was also opinionated, inflexible and not very intelligent and after a disastrous visit to the General Motors headquarters in Detroit Platt commented further that it would be difficult to imagine anyone less likely to get on with middle western Americans. Unsurprisingly, early in 1928 Percy Kidner resigned and took A J Hancock with him, this left General Motors in the rather awkward situation of having an American as Managing Director of Vauxhall. This inevitably reignited the rumblings of protest in the motoring press about the amount of American influence in the British car industry.

Once the decision had been made for the Vauxhall expansion Alfred Sloan personally told Mooney to pick an Englishman to run Vauxhall, according to Maurice Platt Mooney told Sloan that it had better be Charles Bartlett, he’s about as English as they come. Bartlett was Managing Director of General Motors (Hendon) Ltd at the time and was appointed Managing Director of Vauxhall Motors Ltd in 1929. The choice of Bartlett was an inspired one, although very much a GM man fully in tune with the financial & managerial policies of the American company, he possessed the essential ability to interpret the American policy into a British context. This success proved to be hugely beneficial to Vauxhall and the Company moved from strength to strength, becoming one of the “Big six” manufacturers in the 1930s, also fostering some of the best industrial relations in the British car industry which all meant GM gave Vauxhall far more autonomy in managerial decisions than was the case for other divisions of the Corporation.