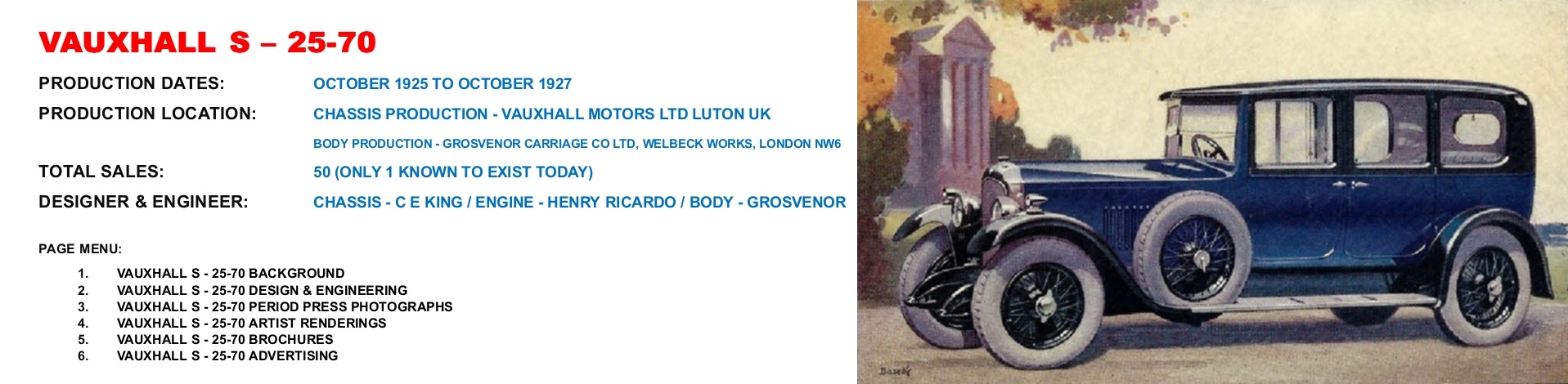

1. VAUXHALL S - 25-70

BACKROUND:

As described in detail in another section of vauxpedia, Vauxhall in the early 1920s was on a downward slide, the market was changing and mass producers were making the motor car more and more affordable. Vauxhall had partially responded to this trend with the launch of the “lower” priced 14-40 and had cut prices on other models but all this meant was the Company sold a few more cars and made next to no profit on each one. In any case, Vauxhall was in no way competing with any mass produced vehicles and the rather inept management were still convinced that the market for larger & more expensive cars would return and demand for Vauxhall’s range of cars would increase – in both cases it didn’t. With an ever more fragile financial position and the very real possibility of the Company being liquidated the Vauxhall Board embarked on the most ludicrous project imaginable given the circumstances. Vauxhall had gained an enviable reputation for building high quality, reliable and generally well-engineered cars that had achieved considerable sporting achievements up to the cessation of competitive activities in 1923, the braking systems employed were the only real aspect where Vauxhall models lagged behind their direct rivals. Both the continued existence of the Company and the hard earned reputation of its cars were put at risk by the new project – the S Series 25-70.

2. VAUXHALL S - 25-70 DESIGN & ENGINEERING:

By the start of the 1920s there had emerged a generic model for the “normal” design layout of the internal combustion engine. There were obviously variations and innovations tried by different manufacturers, a few of these worked but unfortunately many didn’t, but this was a time of when the methods used for machining and assembling engines were relatively primitive and flexible so frequent design changes could be made without the need for costly re-tooling as is the case today.

The established method for the fuel air mixture entering the combustion chamber and the resultant burnt exhaust gases leaving was by means of a “poppet” valve either mounted in the head (OHV) or on the side of the engine (Side Valve) or any combination of the two, further the camshaft could be mounted in the block with pushrods & rockers or with the camshaft mounted above the valves in the head (OHC). The poppet valve got its name quite simply because it is the valve, complete with stem, “pops” in an out of a machined hole. The advantages of this system being effective sealing when combined with a powerful spring even under relatively high compression ratios, extremes of heat and high engine speeds. Effective as this system was proven to be, being still in almost universal use today, it didn’t deter engineering entrepreneurs experimenting with alternative systems.

In 1922 one such man, Roland Cross, invented & patented a rotary valve which was claimed at the time to outperform the poppet valve in a number of important respects. The first full scale trial was made using a single cylinder air cooled engine similar to that used in motorcycles, the valve was fitted on the top of the cylinder head and driven by chain from the crankshaft. As it rotated, passages in the valve allowed fuel air mixture to enter the cylinder & exhaust gasses to leave via the correct ports. The valve system was able to operate at speeds of up to an incredible 7,000rpm even if nearly all the engines at the time couldn’t, or not for very long anyway. Initial results showed it was very smooth & quiet, operated at low temperatures even at high engine speeds but became very erratic at lower rpms. With further development using four-cylinder water cooled engines in cars Cross came close to overcoming most of the shortcomings, such as lubrication, but not the crucial & essential function required of a valve – adequate & proper sealing. Itala and Darrraq were two car makers that tried the idea only to abandon it shortly afterwards.

In 1922 Vauxhall built 3 special cars to compete in the 1922 Isle of Man TT race, these were of a highly advanced design capable of very high performance with a 3litre engine and Westinghouse air operated brakes. The engine was unbelievably advanced for 1922, but sound in conception, and was designed by Henry Ricardo. Rigidity was combined with lightness by the deep aluminium crankcase, aluminium block with cast iron wet liners. High mechanical efficiency was achieved using six ball type main bearings supporting the crankshaft which incorporated a central flywheel and roller big end bearings. Volumetric efficiency was also high thanks to twin overhead camshafts which operated 4 valves per cylinder, masked inlet valves, a dual choke carburettor feeding a mixture to a divided inlet manifold. The 2996cc 4-cylinder engine used a bore of 85mm and 132mm stroke and produced 129bhp@4,500rpm which gave the car a top speed of 112mph. The engine was a masterpiece of advanced engineering design, was years ahead of its time and a credit to Vauxhall. It also cost a fortune to make 3 of these engines for the TT cars, 2 of which retired in the race while the other finished 3rd.

Towards the middle of the 1920s the only limited competition for an alternative to the widely used poppet valve were two separate designs of sleeve valve systems; the Silent Knight double-sleeve valve, invented by an American, C Y Knight, and the Scottish Burt McCullum single-sleeve valve arrangement. The sleeve-valve worked by surrounding the piston with large tubes running the full length of the cylinder which were filled with either the fuel / air mixture or exhaust gasses through two triangular openings in the cylinder sleeve. Minerva in Belgium and Daimler in Coventry used the Knight system many years, Argyll were the best known for using the Burt McCullum single-sleeve system along with Arroll-Johnston in Scotland as well as Picard-Pictet in Geneva, the main advantages of both were quieter & smoother and more economical operation.

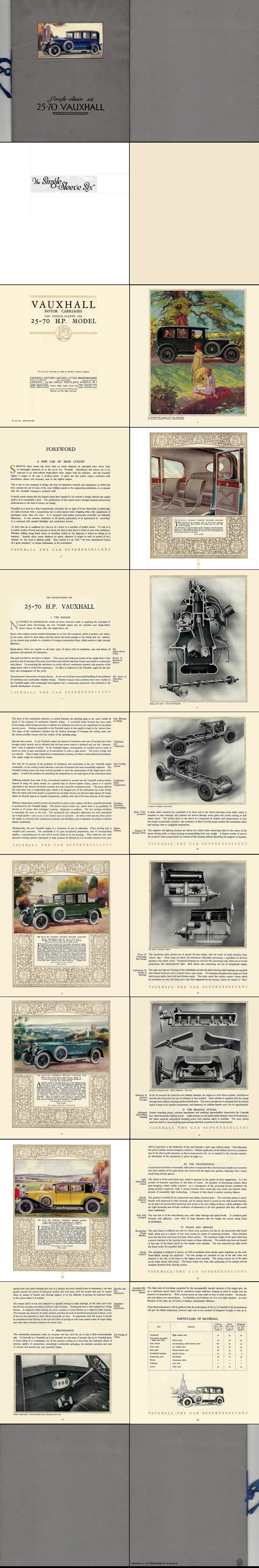

Henry Ricardo was again hired by Vauxhall to design the engine for their new car, the design requirements were for a six-cylinder engine of exceptional smoothness with a target power output of at least 70bhp. Work started early in 1924 with experiments with the less complex single sleeve system on an inline six-cylinder prototype engine. Ricardo had found a new advantage in the single -sleeve valve system, the lack of a red hot exhaust poppet valve gave him the freedom to design a combustion chamber shape without the need to be concerned over the risk of pre-detonation. The engine featured a new conical frustum combustion chamber shape with the spark plug located at the apex in relation to the piston which also meant the new design of cooling water jacket was as close as possible to the spark plugs and worked in the opposite direction in the head to standard practice at the time which ensured controlled temperature distribution across the whole cylinder head. Engine component balance was taken to new heights, every part was specifically selected, weighed and corrected if required. The huge crankshaft was extremely rigid with each web counterbalanced and sat on no less than 10 main bearings lubricated by a pressure fed oil system, it was claimed to be almost immune from wear and it probably was. A silent chain specially developed by Skefco was used to connect the front end of the crankshaft to the sleeve operating worm shaft which was mounted on 9 bearings and drove the sleeves through a combination of worm gears & cranks operating at half the engine speed. A further silent chain driven off the sleeve shaft was used for the magneto & lighting dynamo which was enclosed in same housing which could be rotated to compensate for any chain slack. Special die-cast aluminium pistons were used with three rings the lower of which was to prevent oil passing to the piston crown. The inlet & exhaust manifolds were arranged as two three cylinder engines with no interface between the front and rear trio of cylinders. The engine used an 81.5mm bore and 124mm stroke giving a total capacity of 3881cc and produced 70bhp@2700rpm. Following traditional Vauxhall practice the engine was a very good looking power unit with neat pressings and as much ancillary items enclosed as possible, it was also of a compact overall size considering its large capacity. Although not advertised, Vauxhall anticipated a decoke would be required every 25 to 30,000miles as opposed to the normal 10,000miles which was the average at the time. The Burt McCullum single-sleeve system was patented so Vauxhall had to pay royalties for using it. On paper the 25-70 engine was carefully designed and equally carefully assembled, theoretically the ideal smooth, quiet power unit for a large and heavy prestige car.

Breaking new ground with the engine was matched by the 25-70 braking system, never a Vauxhall strong point, because for the first time self-adjusting 4 wheel hydraulic brakes were fitted. The front brake pistons and cylinders were controlled by heavily loaded piston ring which had a clearance in the piston groove sufficient to let the brake shoes return to the free position after application. To follow up lining wear the rings were forced down the cylinders by the pistons, thereby giving automatic take-up. Acting simultaneously with the front brakes was a contracting transmission brake for the rear wheels. The handbrake was mechanically actuated independently of the hydraulic system and acted on the rear wheel drums. Great claims were made by Vauxhall as to the efficiency of the system which again, on paper, brought the 25-70 into line with rival models. The same system was also used on the last of the 30-98 models.

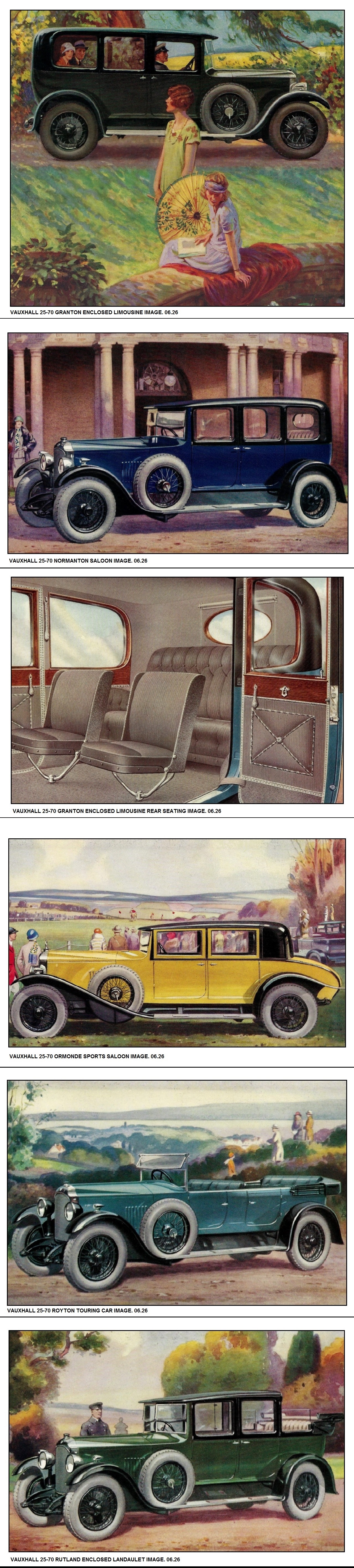

Unlike the rest of the 25-70 the transmission was conventional with a 4speed gearbox driving through a twin plate clutch that was balanced in the same way as the engine to ensure the greatest possible smoothness. The semi floating rear axle was fitted with roller bearings and spiral bevels as well as an aluminium cover plate, the final drive ratio was 4.0:1. Semi elliptic leaf springs were employed all around the car with friction dampers and the steering was by worm & wheel, all normal Vauxhall practice at the time. The massive chassis was made from pressed steel with a wheelbase of 136ins, width of 73ins and an overall length of 180ins. All the bodywork was designed and supplied by the Grosvenor Carriage Co with a variety of body styles from enclosed limousines, landaulets, sports saloons and tourers. Each one was trimmed to a very high standard of luxury and quality.

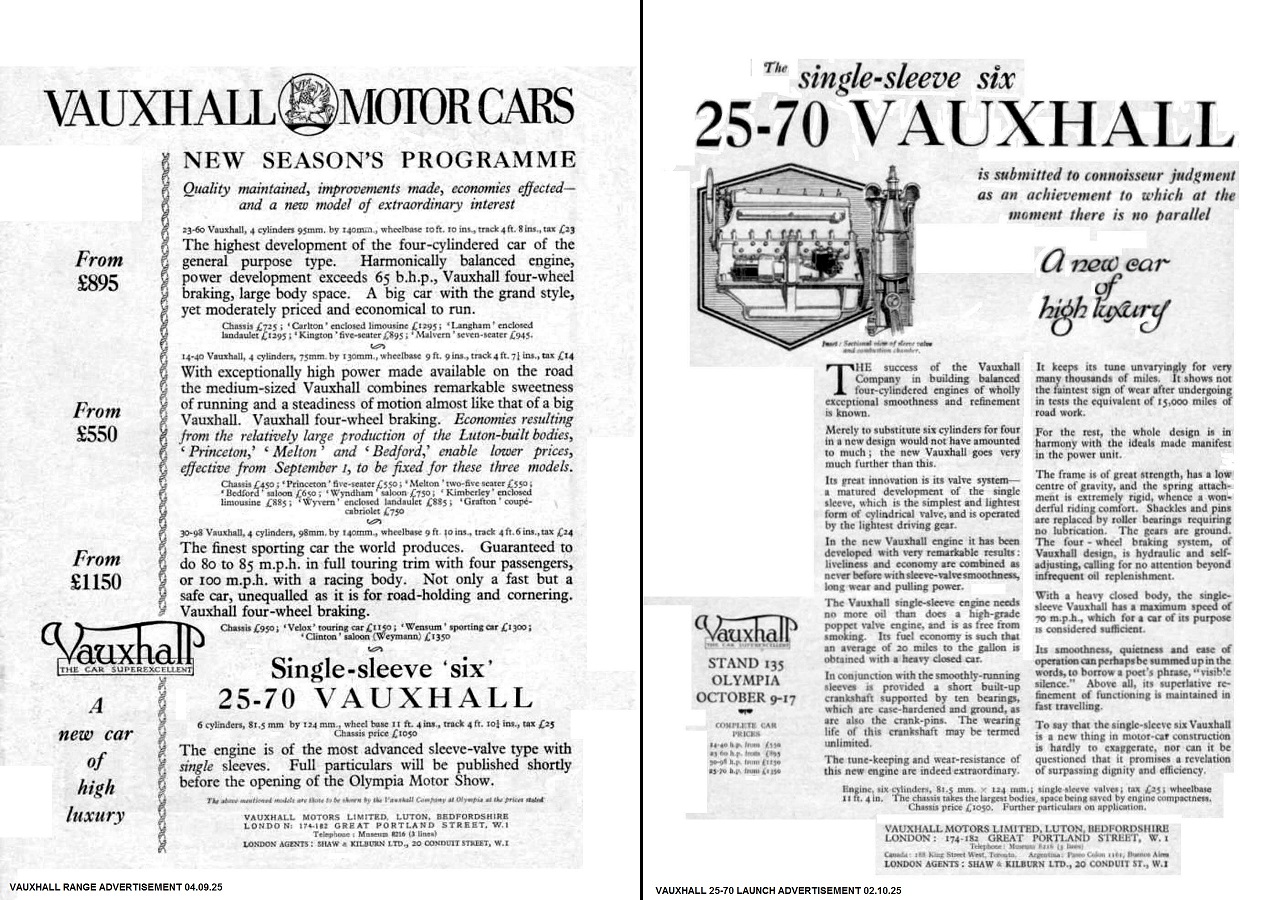

The 25-70 was first mentioned in Vauxhall advertising on 4th September 1925 ahead of the full press & public launch at the Olympia Motor Show in October. Reaction from the both the press and public was one of stunned disbelief, from the press at the impressive specification and claims by Vauxhall about what the car could do and from the public that Vauxhall were trying to sell a car, the Rutland Enclosed Landaulet for example, for a price that was within £250 of a Rolls Royce Phantom. Vauxhalls reputation was good at the time but not that good. Claims made about the new engine’s smoothness & power were true (when it was new) the problem was when fitted to a 25-70 chassis and body weighing in at 2.5 tons with passengers the much vaunted power was only just enough, the car would cruise at 60mph and given enough time could reach 70mph, which Vauxhall self-righteously claimed was sufficient for such a car, however the acceleration was leisurely especially when fully laden or climbing a steep gradient. But that was just the start, despite all the care that went into the manufacturing & assembly of engines within a very short space of time, 2,000miles at worst, the 25-70 would leave a trail of blue smoke behind it and oil consumption would begin to approach that of fuel, as well fouling the spark plugs to the point where they would need cleaning before the car would start. Sleeve valves were an engineering aberration to all motor car makers that used them and for Vauxhall it was just as bad, worse in fact because of the huge price being paid for something that patently didn’t work properly. If the engine were to be manufactured today with the vastly improved tolerances in manufacturing it probably would have performed as intended, but in the mid-1920s the required tolerance levels could not be achieved. Hydraulic brakes were in their infancy and the pioneering effort by Vauxhall was also doomed to fail for two reasons; one how to keep the fluid in the system and two how to keep the air out – a major problem on a car weighing up to two and a half tons. It is not known how much was spent in development but the engine alone would have been prohibitively costly as well as being anything but cheap to make. The farce was clear evidence that the Vauxhall Management had completely lost the plot, in fact a month after the 25-70 was launched they lost the Company as well – because General Motors bought it and if they hadn’t it is almost certain that Vauxhall would have been finished. As for the 25-70 it was the complete opposite of what GM wanted Vauxhall to make, the car was listed until October 1927 and over 2years total sales amounted to just 50 with the last 5 examples being sold off through the motor trade at a fraction of the list price. Only one 25-70 is believed to have survived until today.

3. VAUXHALL S - 25-70 PERIOD & PRESS PHOTOGRAPHS:

4. VAUXHALL S- 25-70 ARTIST RENDERINGS: